Fridiego

by Deborah Brand Probst

If you ask anyone if they are an art lover, my guess is that nine out of ten would say yes. Not many people would confess to not really liking or caring about art. However, there’s a lot of grey area in what loving art actually means. Are you someone who avidly visits museums? Do you collect art? Do you invest in pieces? Do you actively seek out new artists? Or do you simply appreciate things that you consider beautiful, attractive, or emotionally moving?

Being an architect by training, and having spent my entire life in the creative fields, I fall somewhere in the middle of the art lover spectrum, especially when it comes to travel. I’ve taken buses to a remote town in Northern Italy to visit the home of the sculptor Canova, yet I’ve never been to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York despite having visited the city hundreds of times.

On one trip to Spain, I visited three different Picasso museums. And I likely will revisit those same museums every time I return. So, as far as art lovers go, I have my obsessions, to say the least. Pablo Picasso, Egon Schiele, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Salvador Dalí, Leonardo da Vinci, Gustav Klimt, and Andy Warhol are among my favorites.

A Woman Named Frida

And then there’s Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón, known to you and me as Frida. Even non-art lovers are familiar with the flowers in her hair, the endless self-portraits, the floor-length dresses, and that iconic unibrow. Among the many fantastical self-portraits she created, my personal favorite is the photograph by Tina Modotti. There she sits, braiding her hair, exuding an unadorned fragility, free from the usual adornments of dresses, flowers, and that piercing stare.

She transcends the label of “artist” and has become an enduring global phenomenon. More than just a painter, she’s a cultural and fashion icon, a pop star, an activist, a muse to more than just Diego Rivera, her husband and comrade. This Communist, bisexual Mexican artist is perhaps more famous for her distinctive unibrow than for “The Two Fridas,” arguably her most celebrated painting.

The Facts

If you ask your AI tool about Frida, this is what comes up: Frida Kahlo was a Mexican painter best known for her self-portraits and her works that explore themes of identity, gender, and politics. Born in Coyoacán, Mexico City, in 1907, Kahlo suffered a serious bus accident at the age of 18, which severed her spine and left her with lifelong pain and mobility issues.

During her recovery from the accident, she began painting, using art as a means of expressing her pain and experiences. She married the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera in 1929, and they embarked on a tumultuous relationship that spanned over 20 years. Throughout her life, she endured numerous hospitalizations due to multiple miscarriages and surgeries. Kahlo passed away in 1954 at the age of 47.

The Work

Characterized by vibrant tropical colors and dreamlike imagery infused with overt symbolism, Frida Kahlo’s artwork is often described as “folk surrealism.” She drew inspiration from both Mexican folk art and European surrealism. Kahlo’s paintings frequently explored themes of identity, gender, and politics.

A strong and independent woman, Kahlo’s work often reflected her own experiences as a woman in Mexico. She was also a vocal political activist, and her art frequently expressed her views on social justice.

Confined to her bed for extended periods due to her injuries, her self-portraits became a primary focus of her artistic expression. These works, emotional explosions onto canvas, demonstrated a remarkable resilience, showcasing strength and vulnerability despite her physical limitations. Despite her injuries, Kahlo was a prolific artist, creating over 150 paintings during her lifetime. Her work has been exhibited in renowned museums worldwide.

Then There Was Diego

“My husband, my lover, my brother, my father, my son, my friend.“ – Frida Kahlo about Diego Rivera

The celebrated Rivera, 36 years old, internationally renowned and married, met the diminutive 15-year-old Frida, an art student at the time. Their encounter ignited a passionate affair that ended Rivera’s marriage and ultimately led to their own.

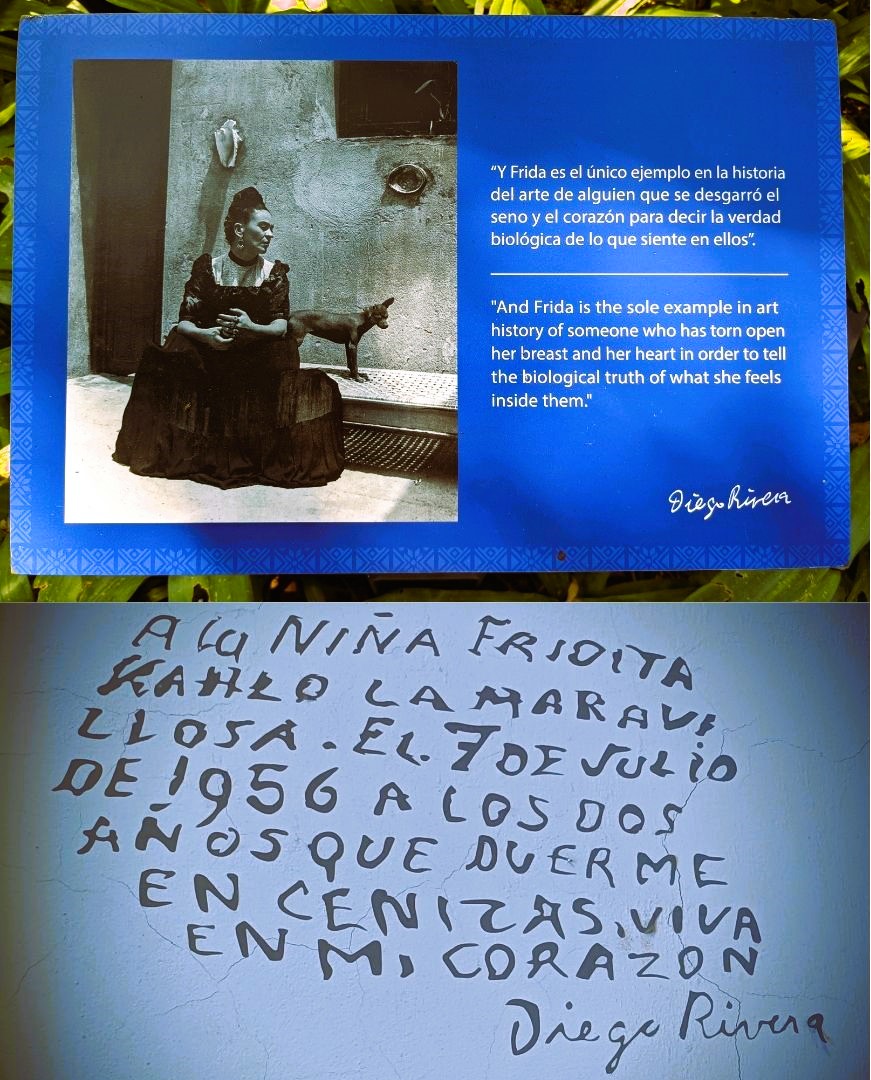

Throughout their lives, they would feature prominently in each other’s art, even as their relationship was fraught with infidelity, divorce, and reconciliation. Inextricably bound to one another, they served as muses, sources of both inspiration and profound pain and suffering.

Rivera’s infidelities, particularly his five-year affair with Frida’s sister, Cristina Kahlo, are widely believed to have been a chronic source of pain for Frida, reflected poignantly in her paintings. However, it’s equally well-known that his love for her was boundless, and she served as a powerful catalyst for his creativity, just as he mentored her artistic development.

In a poignant testament to their enduring bond, Rivera painted a mural of Frida on the wall of her hospital room while she lay in a coma following her bus accident.

The Work

The Palacio Nacional in Mexico City houses some of Diego Rivera’s most magnificent works. He is best known for his murals, rife with political symbolism and overt populist themes of social justice and the exploitation of the common man.

Rivera is one of the most successful Mexican artists of all time, commanding massive fees for his commissions by governments and corporations worldwide.

Together, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera’s representation of everyday life in Mexico introduced an aspect of Mexican and Aztec culture to generations. But here in this grand space, I quietly reflect on “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central,” where you see the child Diego with Frida, depicted as his mother, accompanying La Calavera Catrina.

The Blue House

In the Colonia del Carmen area of the Coyoacán borough in Mexico City, lies a striking blue house in a residential neighborhood. This house, once home to Salvador Novo, Octavio Paz, Mario Moreno, Leon Trotsky, and Dolores del Río, is now the Frida Kahlo Museum. It was here that Kahlo grew up and where she eventually died.

Walking through the house and gardens, you encounter her elaborate clothing, designed to alleviate the pain of her broken spine, and the tiny beds and the chair that supported her injured body – objects that appear more like instruments of torture than furnishings belonging in a childhood home.

As our visit coincided with the month of October, a magnificent “ofrenda,” the altar traditionally built to honor the dead, was on display throughout much of the city. You also see the peaceful gardens, the humble kitchen, and everywhere you turn, you sense the presence of Frida and Diego through subtle details throughout the garden. The creation of the museum was the work of Rivera, who, after her death, assembled unseen pieces of their work and stipulated that the museum should only be opened to the public after his own demise.

The Studio

Just 15 minutes away, in the San Ángel neighborhood, lies another Casa Azul – the twin house that Kahlo shared with Rivera for most of their life, and where he continued to reside after she moved back to her childhood home. These twin houses, designed by their friend the architect Juan O’Gorman, sit side-by-side, connected by a bridge where Frida would bring him meals she had prepared in her own tiny kitchen. In contrast, Rivera’s house contained only his bedroom and a massive studio.

The studio’s windows, extending from floor to double-height ceiling, fully opened onto the garden below, flooding the space with natural light and allowing his large-scale artworks to be moved through the window rather than through the house’s doorway. This studio housed his archaeological collection and the works in progress, reflecting the artist’s larger-than-life personality. After Kahlo’s death, Rivera had her ashes placed in an urn within his home. In the end, this giant of a man was broken by the force of nature that was the tiny Frida. ‘I love you more than my own skin, more than my own heart, more than my own soul,’ he famously wrote. He lived in the house until his death in 1957.

FRIDA KAHLO EVERYWHERE

“I’m Frida Kahlo, and you’re my Diego.” – Madonna in the song “Hung Up”

Sixty years after her death, Frida Kahlo’s image, her personal brand, has perhaps never been stronger. She has been referenced by artists, musicians, and writers. From the film “Frida,” where she is portrayed by Salma Hayek, to the fashion brand Rodarte with their Frida Kahlo-inspired clothing collections, to the cosmetics company MAC with their Frida Kahlo-inspired makeup lines, the icon lives on. She has even been immortalized as a Barbie doll.

We encounter her everywhere in our travels and our own personal lives. We see her on the streets of Tel Aviv, in a restaurant in Galway, in the alleys of Tropea, and across Mexico. Her influence permeates various aspects of our lives: at the Voodoo Festival in New Orleans, at my sister’s wedding in Puerto Vallarta, even during a mourning period for a friend’s passing at Dia de los Muertos in Oaxaca.

Her paintings, a riot of colors expressing both pain and resilience, depict her in long dresses concealing the braces that supported her injured body. But it’s the flowers, the iconic unibrow, and the image of this powerful woman – a manifestation of personal expression and triumph in the face of extreme adversity – that truly defines Frida Kahlo as an enduring muse imprinted on our collective consciousness.