Much About Mucha

by Deborah Brand Probst

I am remiss that I knew very little of Alphonse Mucha before I saw the exhibits in Prague. Sure my college art history classes as part of my Environmental Design degree gave me familiarity with his Parisian illustrations which together with Toulouse Lautrec can be said are quintessential representations of Parisian graphic design at the turn of the century. In fact the art nouveau style in Paris has been referred to as “le style mucha.” But I knew very little else about this prolific artist, and as one of Prague’s most celebrated artists, his artwork is shown all over the city in multiple museums. So it is with the theatrical images of Sarah Bernhardt in my mind that we went to the Mucha museum in Prague.

It is there that I discovered that Mucha was an illustrator yes, but also a painter, sculptor, interior designer, packaging and jewelry and furniture designer, photographer, and lastly a patriot. At an early age he was also a musician. A talented violinist and alto singer, he was deeply religious and grew up singing in choirs in the church. It is no coincidence that so much of his work, even the most urbane, have an elevated spiritual quality to them. Rejected by the Academie of Fine Art in Prague, he was forced to leave his beloved country to find his way in Vienna, and then in France. It is here that his illustrious career begins.

“What is it, Art Nouveau?… Art can never be new.” “

Alphonse Mucha

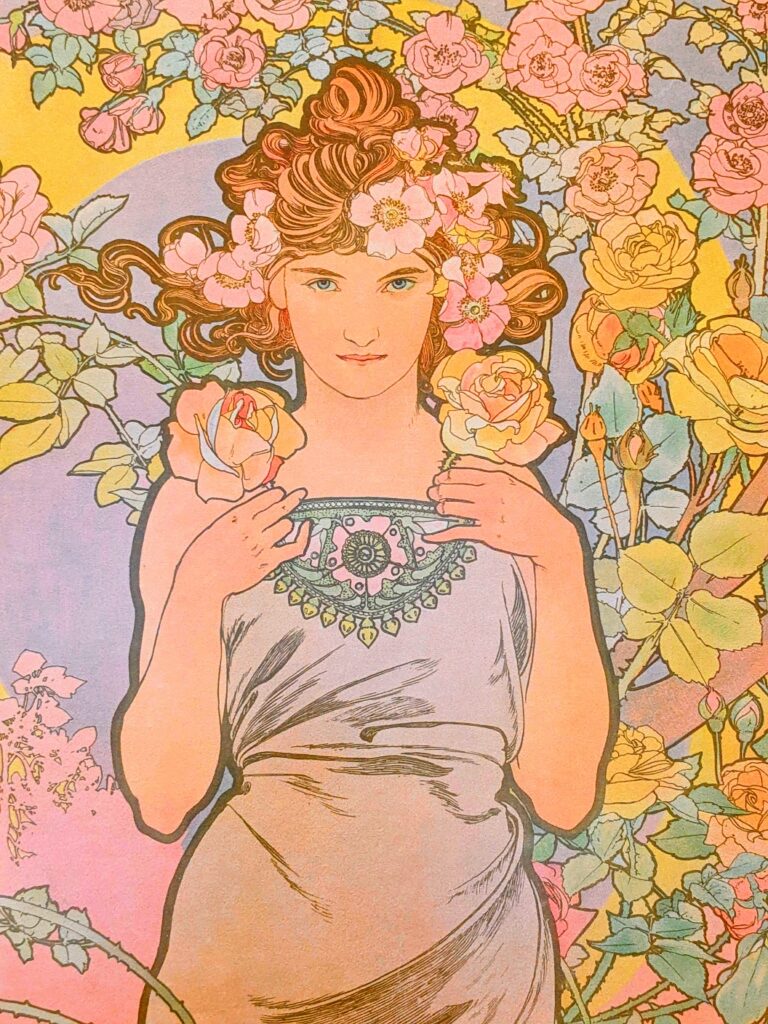

If Victor Horta is the father of Art Nouveau, then Mucha most certainly must be its favorite son. Nowhere is the sinuous flowing plant motifs more prevalent than in the early Parisian art of Mucha. To this day when we think of art nouveau as a decorative artform, “le style mucha” is what comes to mind – botanical back grounds in soft pastels caressing women with cherubic faces in idealized poses. These are the pieces of Mucha of which I was most familiar, the work he created as a young artist in Paris.

“Beauty is a universal language that can be understood by everyone.”

Alphonse Mucha

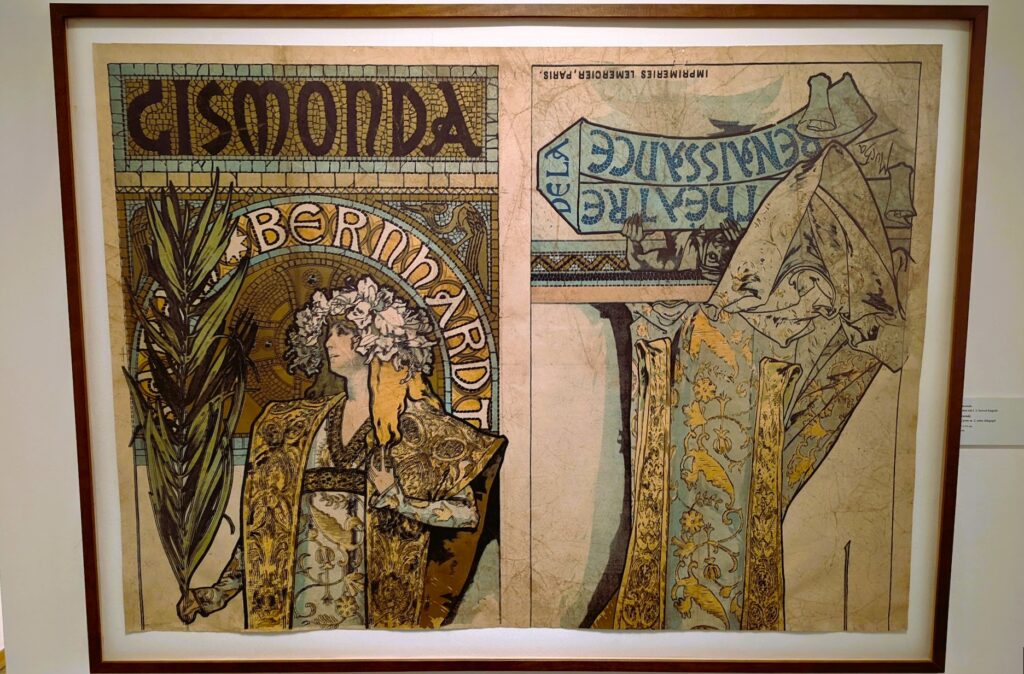

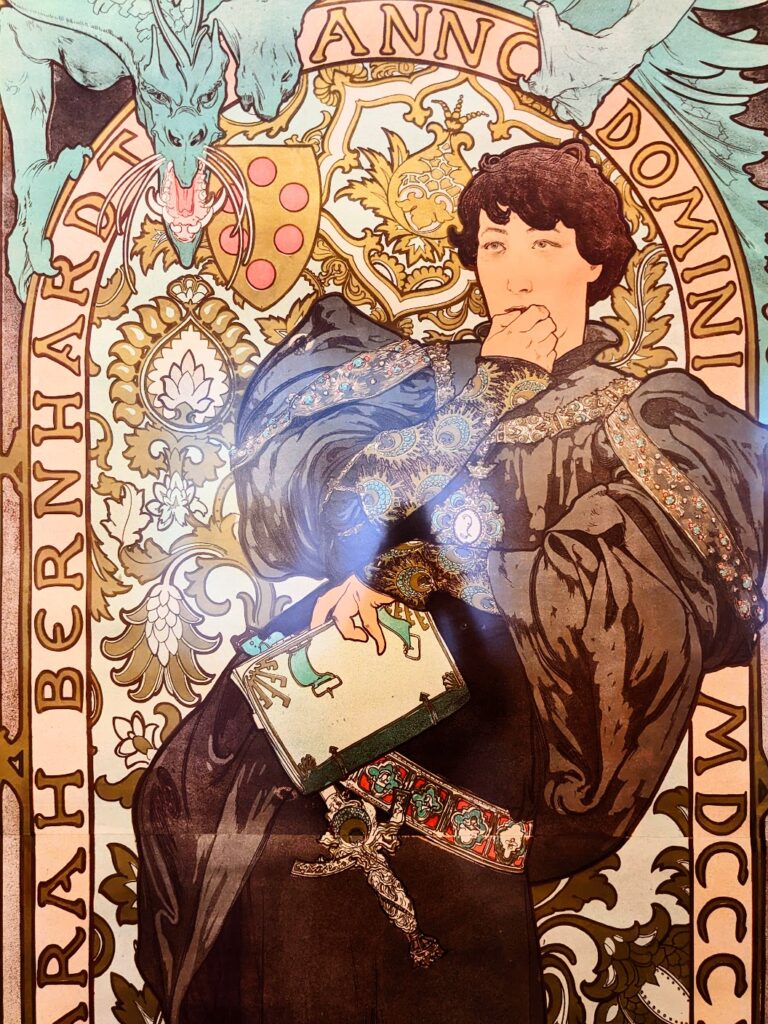

It was Sarah Bernhardt who put Mucha on the map of high society Paris. His posters of her were such a collectors item that people would take them off walls wherever they were displayed to promote her latest theatrical appearance. Much like Yvette for Toulouse Lautrec, Bernhardt was less muse and more collaborator as her costumes on stage lent itself to his theatrical style.

His work for her on Gismonda was truly pure serendipity for he was the only illustrator at the studio when she called to commission a new piece for the show. On the success of that commission, he went on to produce eight theatrical posters with Sarah Bernhardt, illustrating her with a halo/arch in all the pieces elevating her presence and forever cementing their status as mutual icons of the Parisian art Nouveau movement.

“I was happy to be involved in an art for the people and not for private drawing rooms.”

Alphonse Mucha

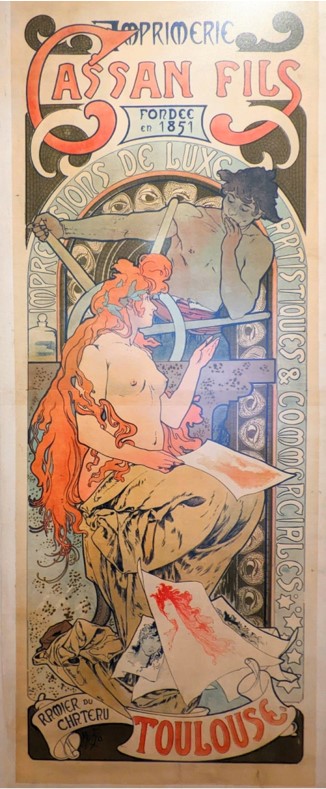

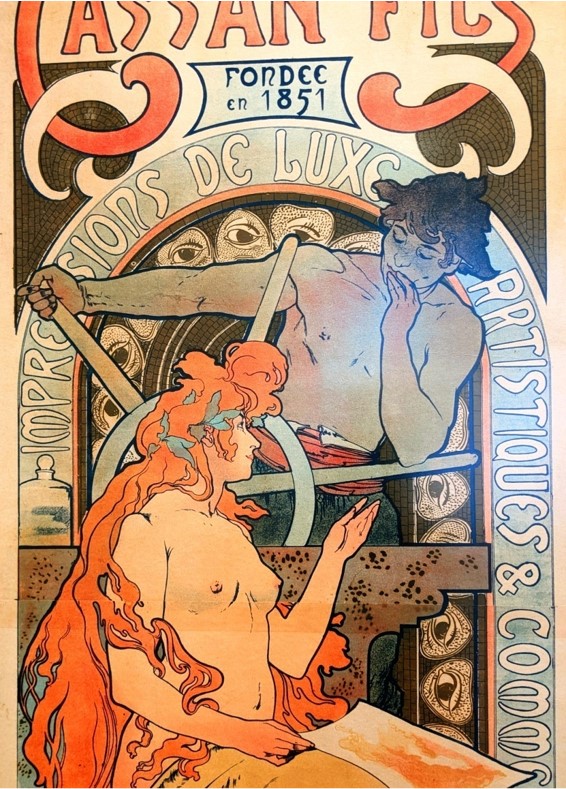

It didn’t stop there. Mucha went on to design posters for products. He designed posters for cigarette papers, champagne, biscuits, baby food, chocolate, beer, brandy, bicycles and in the example shown in the photograph, for the French printing house Cassan Fils. He also created a series of posters that were purely decorative, without text to be sold for a small amount essentially commercializing fine art for the masses.

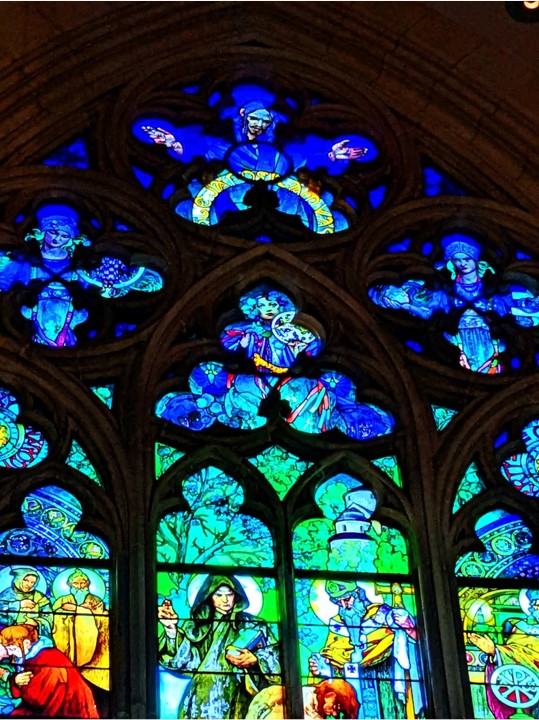

Aside from painting and posters, he designed sculptures, jewelry, stained glass windows, and sets for theatrical productions. He became one of the most successful artist of his time, amassing a body of work with over 1000 pieces during this time.

“When gods are at war, salvation lies in the arts”

Alphonse Mucha

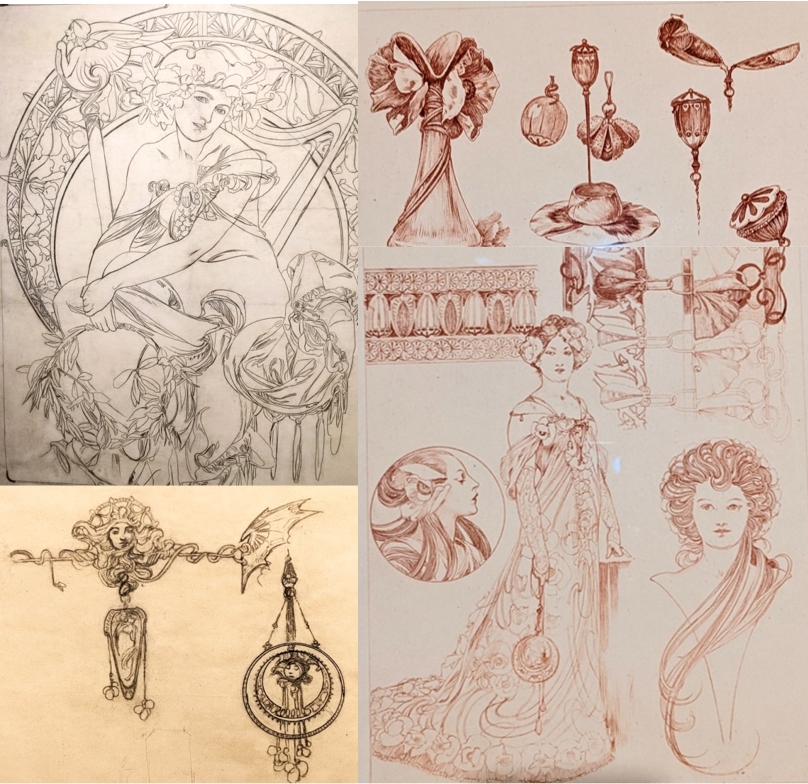

As a trained architect, what struck me even more than the designs and the layers of color in the artwork, was the meticulous drawing, whether it was the design for a pair of ear rings, perfume bottles, costumes, or furniture. The level of precision and work that went into each piece is astounding, and illustrate the precision of his graphic vision.

Mucha was known for his long hours and his dedication to his art. He would often work 12-14 hours a day, and often seven days a week. He was also very disciplined as evidenced by the process he would go through to create every single piece – from sketch to detailed drawings, photographs, layer and layer of color studies until he would finally land on the final piece. And unlike many master artists of the time, the amount of time he himself spent on each of the productions was astounding.

“The purpose of my work was never to destroy but always to create, to construct bridges, because we must live in the hope that humankind will draw together and that the better we understand each other the easier this will become.”

Alphonse Mucha

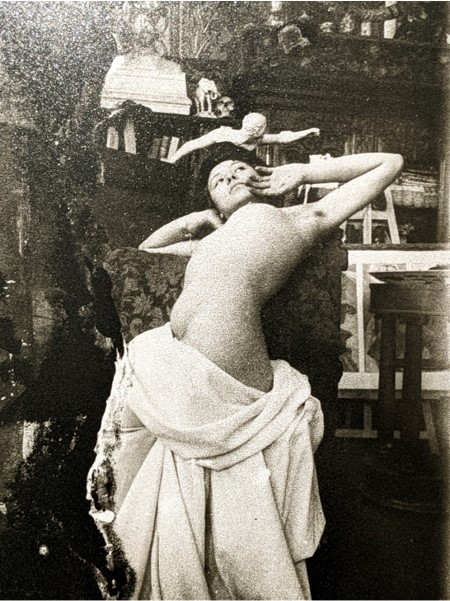

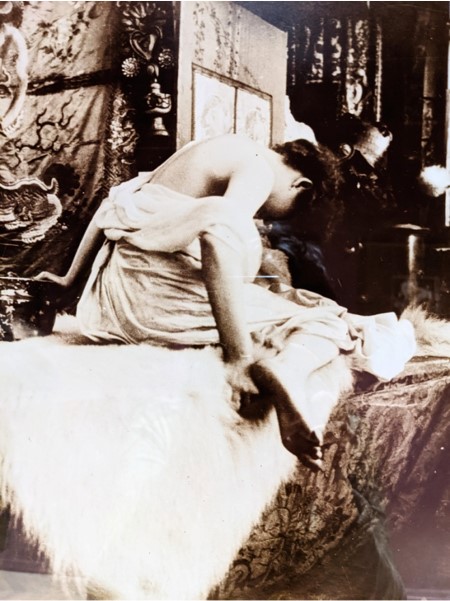

Mucha used photography in the same way he used his drawings, as a means to study the subject in the process of creating the final piece. He didn’t consider his photographs art in themselves and never touched them up. The elaborate and precise way he staged his models, complete with costume and artfully designed backdrops in his studio, resulted in photographs that were visual feasts in and of themselves. If he had chosen photography as his medium, I have no doubt he would have been a master photographer as well.

“The human spirit is eternal and will always triumph over adversity”

Alphonse Mucha

When Mucha finally came home to Prague after his time in Paris, he continued his prolific creative pace with pieces depicting his native Slavs.

For the independent country of Czechoslovakia after World War I, he designed the first Czechoslovak stamps, and the country’s first banknotes. He did not ask for compensation for this work and it would go on to be his most duplicated work.

He also completed his most ambitious piece. The Slav Epic, a series of 20 large canvases that depict the history of the Slavic people from their pagan origins to their struggle for independence, Mucha’s art was often associated with Czech nationalism. For this reason he was held and questioned by the Nazis several times after the Nazis annexed Czechoslovakia. Mucha died before the end of World War II.

“Art exists only to communicate a spiritual message.”

Alphonse Mucha

In the Cathedral of St Vitus in Prague, high on the hill, Mucha’s piece stands out among the stained glass windows, a culmination of a lifetime of work for a country and a city that once rejected, and then later celebrated him as an artist and a patriot.

Mucha’s religious beliefs were an important part of his life and work. They helped to shape his worldview and his artistic vision. His work is a celebration of beauty, truth, and goodness, and it is a testament to his belief in the power of art to inspire and uplift.